When the valley of Padania was cleared, the Benedictine and Cistercian monks began to transform milk into large rounds of cheese which could be matured for a long time. Parmigiano originates from more than nine centuries ago.

Going back as far as Ancient Rome, writers of the time mention the specific area of production of Parmigiano-Reggiano in their texts. It was not until the Middle Ages that precise information was noted down, explaining that in the abbeys of the Benedictine and Cistercian monks of the area of Po began the production of Parmigiano-Reggiano, using techniques that are still used today. In particular, in the area of Po situated between the Apennine Mountains and the right side of the Po River, the monks, who were skilful farmers, cleared the marshes and cultivated the fields where they made sure that there was a sufficient amount of fodder for to be able to raise a lot of cows.The Clover and the Lucerne were cultivated in the fields, and are today, still essential in the diet of the cows, and go to create a particularly tasty cheese, with a delicate aroma and a long maturing period without adding additives or conservatives. Parmigiano-Reggiano is made using a large number of cows; one round of cheese is made with nearly 600 litres of milk, which can make a cheese weighing 40 kg.

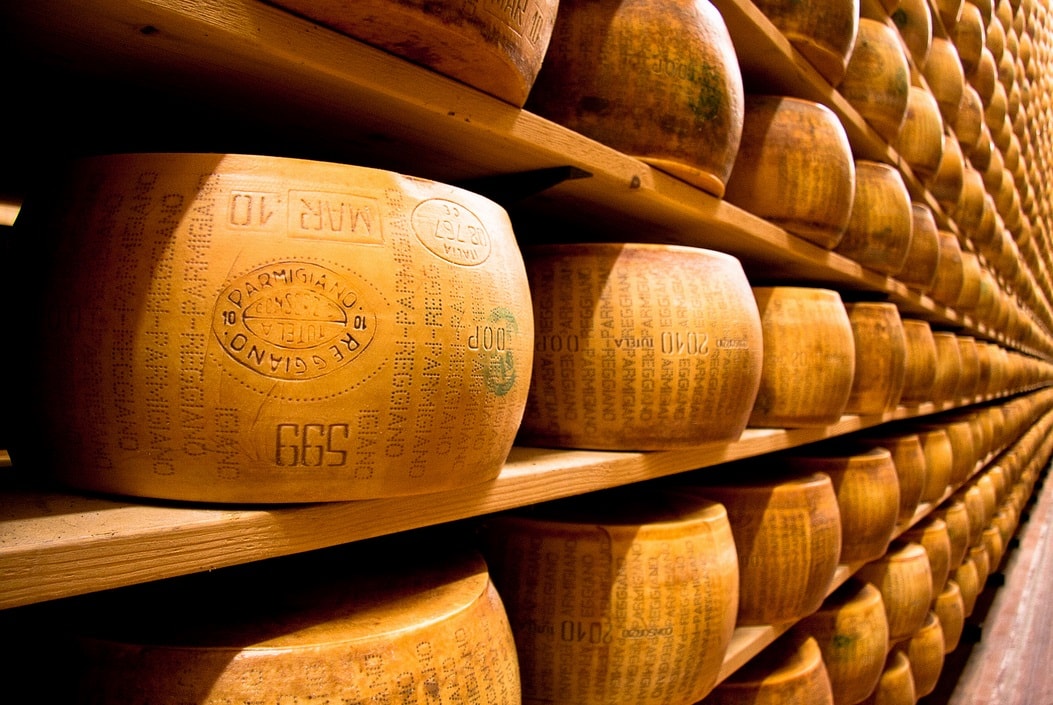

It was alongside the large monasteries and imposing houses that the first ‘caselli’ appeared. These were small, square buildings where the milk was transformed into cheese, and they can still be seen in the countryside today, as they were in Parmigiano-Reggiano in the 12th Century. This period saw the beginning of trading between different religious communities from Italy and the rest of Europe, which led to development of quality food products, which are still enjoyed today. Including beer, eaux de vie, quality red and sparkling wines and excellent cheeses.The monks of Padania discovered that by heating the milk twice to a controlled and adapted temperature, when the cheese is made, it contains little water. This was ideal for making a cheese which could be conserved for a long time, and gave the cheese nutrition and a good taste. Quickly, the large rounds of Parmigiano-Reggiano, golden like the sun, attracted the attention of the traders and the cheese was then enjoyed throughout the world. Since, the production of Parmigiano has hardly changed because it is in the respect of the traditions that make this cheese what it is.

There are a number of documents attesting to the ancient origin of the Parmigiano-Reggiano.

From Ancient Roman times, Columella, Varrone and Marziale wrote about the fabrication and the name of a cheese from Parme presenting the same characteristics as Parmigiano-Reggiano. One of the most convincing citations is found in the ‘Decameron’ by Giovanni Boccacio. In the book, Maso refers to Parmigiano whilst he is describing the region of Bengodi in Calendrino. This is the Parmigiano-Reggiano as we know it today.

The bright idea to season pasta with the cheese is a tradition which dates back to ancient times, as Brother Salimbene attests in “Les Chroniques.”

Giorgio Vasari writes that one evening; Andrea del Sarto presented a small temple with 8 faces, like that od San Giovanni, but mounted on columns. The floor was a large plate filled with mosaics of many colours. The columns seemed to be like large sausages and the top and bottoms were Parmigiano.

Gaspar Ens, in his Deliciae Italiae of the 16th Century, wrote that the area around the town is very fertile, rich in cereals and many kinds of fruit, but the wine, oil, milk and cheese are especially infamous throughout the world. He also wrote “at this time, the pride of Italy is the cheese Parmigiano.” In 1656, in the dictionary of synonyms by Francesco Serra it reads; “the names of cheeses come from the places that best describe them; like the Parmigiano, which takes its name from the area where it is best.”

In one of his recipe books, Cristoforo di Messiburgo describes the evening of 17th January 1543 as a simple, small gathering, amongst friends, where the 6th course consisted of Parmigiano cheese. The cheese was served with grapes and pears. Just like today, where the cheese is served with fruits, as a gourmet dessert.

François Leblancin, in his Memoires, says that the pasture is so large with plenty of food, that it can feed an incredible number of cows, who produce the milk for this infamous cheese, known the world over, and sold at an incredible rate. John George Keysler, in 1760, writes that the Parmigiano, coming from excellent pastures of the countryside, is present on the most elegant tables in Europe.

Parmigiano-Reggiano was recommended for children and old people because it was so nutritious, easy to digest and very high in calcium and phosphorus.

Giacomo Casanova (1725-1798), in his ‘Story of my life’ of 1797, writes “I was dying of hunger, and they told me they had nothing to eat. But convinced this was not true, I ordered the innkeeper, to which he laughed, to bring butter, eggs, macaroni, ham and Parmigiano cheese, because I know that these things can be found anywhere in Italy. But the most indisputable account, comes from the manuscripts from the archives of Reggio Emilia and Parme, where the documents which record trade and exports refer to the shipments of Parmigiano-Reggiano which were sold throughout Europe.

In his book, ‘The Italy of Today’ from 1859, Edmund Roche wrote “We went to the Inn of the post office, which had been recommended by a friend, and we ate a meal of cheese, the veritable Parmigiano: a fatty soup made of cheese, mutton with the cheese, a cheese omelette, macaroni (naturally with cheese), cheese as dessert, and all accompanied by a wine which went to the head and of which we consumed in large quantities due to the thirst that the meal created.

In Spike Hughes’ ‘Out of Season’ of 1956, the author writes; “You should go to Parme- they tell us-it is the place where you eat the best in Italy. We had one of those meals that you remember for the rest of your life without being able to describe exactly everything that was eaten... The owner brought us veal enveloped in a sort of coat of Parmigiano, covered with white truffles giving the most beautiful decorative effect.”

Gianni Brera, wrote in ‘La Repubblica’ in 1989; “I have a fabulous restaurant in mind in which I found refuge after the sublime interlude (cathedral and Baptistery)…. And finally the innkeeper showed me a rustic morsel of Parmigiano. The knife cut to the heart of the cheese…Immediately, a sumptuous burst, the ochre granite of the surface…I left Parme brimming with the feeling that I felt at home. I carried with me a souvenir linked intrinsically to pleasure…”